The Presbyterian South China Mission

An Organizational Study

Introduction

The Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions (PBFM) was an organization under charge of the Presbyterian Church (USA) that commissioned missionaries and missions in foreign and domestic lands. One such mission that was under charge of the PBFM was the South China Mission, headquartered in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China (廣東省廣州市). This mission did a variety of work in Guangdong province, Hainan province, and other surrounding areas.

The focus of this study will be the South China Mission and the work it did, contextualizing it within the PBFM and other missions in China. This study will also focus on the decades ranging roughly from the 1840s to the 1890s, as the documents available to synthesize information for this study mostly concern this time, even though the South China Mission continued work for decades after the 1890s. The largest body of primary source materials for this study come from The College of Wooster’s Department of Special Collections—specifically its Noyes Collection, an archival collection of manuscript materials from the Noyes family, a prominent family within the South China Mission and the Presbyterian Church in Ohio, as well as the Missionary Alcove Collection, a special collection of published materials used for educating future missionaries during the late 19th and early 20th centuries when The College of Wooster trained missionaries to go abroad and do mission work. A body of secondary sources is also used for this research, including a finding aid for an archival collection belonging to the Presbyterian Church (USA) and secondary scholarship on mission work.

In this organizational study, I will examine the history of both the PBFM and its South China mission, describe its organizational structure and organizational values and culture, and provide feminist, post-colonial perspectives on the work done by the PBFM’s South China Mission.

History of The Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions (1837-1958)

The PBFM was organized in 1837 by the Presbyterian Church (USA), an action of the Old School of the Presbyterian Church.[i] At this time, the PBFM was not yet a legal entity, not being incorporated as such until 1862. During the years before 1862, the PBFM was a “benevolent society of the Presbyterian Church,” meaning it was a committee within the Church’s administration.[ii] The mission of the PBFM during this period was “to convey the Gospel ‘to whatever parts of the heathen and anti Christian world, the providence of God might enable the Society to extend its evangelical exertions.’”[iii] In 1862, the Board was finally incorporated as a legal entity within the state of New York.[iv] By the 1920s, the PBFM had missions located on the continents of Africa, Asia, South America, and North America.[v] The PBFM ended its tenure in 1958 when it was incorporated into the Commission on Ecumenical Mission and Relations under the United Presbyterian Church of the United States of America.[vi]

History of the South China Mission (1845-1890)

The first missionary to be commissioned for work in South China, was Dr. Andrew P. Happer, who arrived in China with his wife in approximately 1845 in Macau, opening a boarding school for boys in the same year.[vii],[viii] In 1847, Dr. Happer and his wife moved their work to Guangzhou, where they stayed for many years.[ix] This marks the beginning of the South China mission under control of the PBFM. Following opening the boarding school in Macau, Dr. Happer also taught English in a Chinese Imperial Government school, as well as opened a hospital and dispensary in 1851 in Guangzhou.[x] The mission force, after nearly ten years of doing work alone under the PBFM, grew to five with the arrival of Dr. John G. Kerr, his wife, and Mr. Preston in 1854.[xi] At this time, Mr. Preston began street preaching, and Dr. Kerr immediately took over the hospital that had been run by Dr. Happer previously.[xii] The mission did not grow more until 1860, when Rev. Condit and his wife arrived in China, and in 1863, Rev. Folsom and his wife arrived. It was originally intended for these new missionaries to set up a sister mission in Foshan, Guangdong (廣東省佛山市, 12 miles from Guangzhou, then called Fat Shaan by English speakers), however, this never came to fruition, although other Christian denominations did set up missions in Foshan.[xiii]

A new era of the South China mission began in 1866 with the arrival of Dr. Henry Varnum Noyes with his wife. These missionaries were the last of the South China Mission to arrive in China by sailboat, as steamers commenced running lines between the United States and Japan, as well as Hong Kong in 1867.[xiv] I mark his arrival as a new era of mission work by the South China mission due to Dr. Noyes’ increased attempts to go further inland to do mission work, something that had been extremely limited by the Chinese Imperial Government for many years beforehand, and still was at the time.[xv] However, Dr. Noyes still attempted to go further inland from Guangzhou, a city that sits on the Pearl River Delta, and would land his boat (as most travel inland was by boat at this time) wherever he was allowed. However, this did prove dangerous at times. According to Harriet Noyes, there was at one point a group of ninety-six villages that vowed to “kill anyone who should ever dare to bring a foreigner to one of their villages.”[xvi] Although there were these dangers, Dr. Noyes still would attempt to street preach inland as funds for education endeavors were not available at the time.[xvii] Additionally, in 1867, two mission homes were constructed for the mission, the first to be built according to “western ideas” by the mission, and possibly in all of Guangzhou.[xviii]

The mission force continued to grow, and in 1868, following the death of Dr. Noyes’ wife, his sister Harriet, accompanied by Dr. and Mrs. Kerr who had been on furlough, arrived in Guangzhou. Harriet would prove to be a major boon to the work of the South China Mission, starting off right away opening a day school soon after her arrival. Following Harriet’s arrival and the return of the Kerrs, the mission force doubled in 1870 from six missionaries to twelve. Following the growth of the South China Mission, Harriet Noyes established one of the first boarding schools for women and girls in Guangdong, and possibly all of China, in 1872.[xix],[xx] There had been earlier attempts by Dr. Happer’s wife to do so, but those attempts went unfinished due to sickness in the first attempt, and her death in the second attempt.[xxi] Three years following the opening of the boarding school for women and girls, the True Light Seminary (真光書院, still running now as the True Light Middle Schools of Hong Kong and Kowloon with other sister schools) opened, with a graduating class of nine girls following their three years of study at the Seminary.[xxii]

Following the opening of the True Light Seminary (TLS), in 1873, Harriet had ensured the training of six women to be bible women, Chinese women who went home-to-home in order to spread the word of the Presbyterian Gospel.[xxiii] Continuing work in education, which Harriet deemed to be “the most practicable and satisfactory way of reaching the women and children,”[xxiv] Dr. Noyes opened a boarding school for boys in 1878.[xxv] The mission continued to grow and grow as years went on. By the end of 1879, the mission had 12 missionaries from America, 15 assistant men, 7 bible women, 15 teachers, and 545 students in the South China Mission’s schools.[xxvi] In the following year, 1880, the Mission controlled $10,604 in expenditures——$3600 for 4 married missionaries and their wives, $1800 for 4 unmarried missionaries, $1,140 for 14 assistant men, $294 for 7 bible women, $1,280 for 2 boarding schools, $1,200 for 14 day schools, $500 for 5 language teachers, and $790 for miscellaneous costs.[xxvii] It is clear through these numbers the amount that the South China Mission grew since its beginnings with Dr. Happer in 1845.

However, the mission continued to grow greatly. Happening between 1880 and 1882, the mission received 18 new missionaries—more than doubling the amount of Americans working for the mission.[xxviii] Also, from 1880 to 1885, five new Presbyterian churches in addition to the two that already existed in Guangzhou, and the number of “outstations” in the surrounding areas of Guangzhou grew to twenty-four.[xxix] The number of students also continued to grow, with 636 students in boarding schools and day schools by the end of the 1880s.[xxx] The number of patients being seen at the hospital was also staggering for the small number of missionaries heading up the work—there were 39,500 patients seen in 1887, with over 4,000 surgeries being performed.[xxxi] Additionally, eighteen Chinese students were training to be doctors, with five of them being women.[xxxii]

The work of the missionaries and all those who helped them did not cease at the end of the 1880s, and actually continued until 1946.[xxxiii] It is likely that the mission ceased work at this time due to the civil war occurring between the nationalist Republic of China and communist fighters. I end my study of the mission’s history at the end of the 1880s because further study would be beyond the scope of this project. Harriet Noyes continued her work in China until 1923, just months before her January, 1924 death;[xxxiv][xxxv] Henry Noyes continued his work in China until his death in 1926;[xxxvi] Dr. Happer continued his work until his death in 1894.[xxxvii]

Organizational Structure and Values of the PBFM and South China Mission

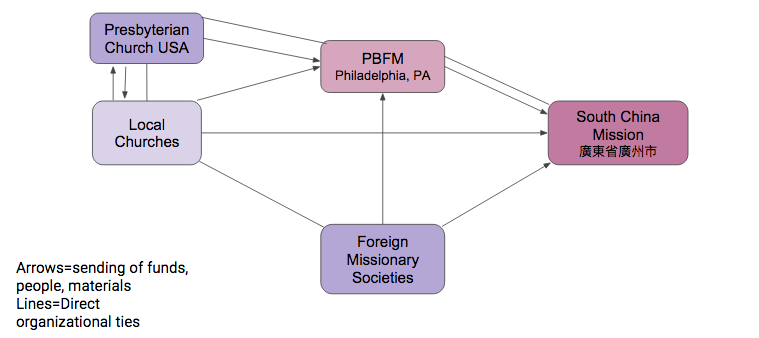

The structure of the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions and its South China mission is quite interesting, and needs to be looked at in the broader context of the Presbyterian Church of the United States of America at the time. The following diagram can help us better understand the structure of the PBFM and its South China mission, as well as how money was distributed to various parts of the organization and where it was sourced. [see image 3.4 at the bottom of this page]

We can trace much of the funding for the South China Mission and the PBFM itself to local churches and Foreign Missionary Societies their parishioners created. Churches could ask parishioners for donations on the behalf of missionaries, and Foreign Missionary Societies would often do different fundraising activities like sewing and sewing quilts to holding banquets.[xxxviii] Funds could be sent from local churches to the Presbyterian Church (USA)(PCUSA), which could then be sent to the PBFM. Funds could also be sent from the local churches or the Foreign Missionary Societies (FMS) directly to the mission, or from the FMS to the PBFM. Often, the PBFM would need to approve major spending, so it is likely the PBFM collected much of the money that was sent to the individual missions.

As it may be clear, the PBFM and its South China Mission do not neatly fit into a certain type of organizational structure. However, according to Kathleen Ianello’s definitions of decentralized and fragmented organizations, the PBFM and South China Mission can be described as a mix between a decentralized organization and a fragmented organization. A decentralized organization, according to Ianello, is one with a bottom-up organizational structure, where some of the major decisions and most routine decisions are made by the lower parts of the organization, i.e., the South China Mission, with the higher parts of the hierarchy, i.e., the PBFM, still make most of the major decisions.[xxxix] However, in fragmented organizations, most of the major decisions are made by the lower parts of the hierarchy, and the upper parts of the hierarchy no longer have much control.[xl] I deem the PBFM and the South China Mission a mix between these two types of organizational structures because the South China Mission would make some major decisions, where the PBFM would make some as well. For instance, the PBFM would approve of a budget for a school for the South China Mission, and the South China Mission would decide how it would be designed architecturally.[xli] However, I also categorize it as fragmented due to the number of major decisions made by the South China Mission.

Relying on archival documents, it is difficult to determine the official organizational values of the PBFM and South China mission as most of the manuscript material is personal correspondence from members of the South China Mission, however, as discussed above, a mission statement for the PBFM itself is available. The mission of the PBFM during this period was “to convey the Gospel ‘to whatever parts of the heathen and anti Christian world, the providence of God might enable the Society to extend its evangelical exertions.’” Here, it is clear that the main motivation for creating these missions across the globe is obviously to evangelize non-Christians. However, the wording of the mission can tell us more about the values of the organization itself. The use of the word “heathen” in the mission for the PBFM signifies an air of superiority and condescension towards non-Christians. Additionally, the use of “anti Christian” reflects the frequent self-victimization some Christian denominations utilize for sympathy. Finally, “the providence of God,” signified how the PBFM views its actions as sanctioned by God himself. Although much cannot be derived from this mission statement alone, there is some valuable information contained within it.

Post-Colonial, Feminist Perspectives

The motivations for mission work were not always well-intentioned, or if they were, they were very often shrouded in attitudes of racism, ethnocentrism, and religious superiority. These attitudes need to be examined to understand the implications of mission work. Although much of the work that was done by the South China Mission can be portrayed easily in a positive light, specifically the educational and medical aspects of the mission work, there was still often an air of the attitudes discussed above by the missionaries themselves.

According to al-Hajri, “’most missionaries were primarily concerned with evangelizing the world first and providing humanitarian aid to foreign people second.’”[xlii] Additionally, al-Hajri argues that “all non-Christians needed to be educated so they could read the Bible and gain the knowledge of Christian beliefs and values.” These two statements about the primary motivations of missionaries in foreign lands show that the purpose behind mission work was never to provide aid to the people where missionaries colonized, but rather to evangelize the people of these nations, and if need be, to provide aid to entice them to evangelize. al-Hajri also specifically addresses the topic of education in their piece: “Education was also emphasized by American Missionaries from the very beginning. If preaching the Gospel was necessary, it was also necessary to spread education so that the Bible could be read and understood.”[xliii]

In addition to the above, the work of missionaries can also be understood in terms of violence. “Apart from praising the gentle ‘gospel of love,’ American missionaries described evangelization, very obviously in many instances, as war… American missionaries… frequently used… words such as ‘war’ and ‘occupy’ in their journals and reports.”[xliv] Furthermore, al-Hajri also states that, “The connection between being martyrs and spreading Christianity indicates the missionaries viewed the work they were performing as a war in which they must win over other religious groups. Any interactions that happened with non-Christians were interactions with the enemy.”[xlv]

We must also understand the mission work being done in the South China Mission as orientalist in nature. Orientalism, according to Edward Said, who coined the term, should be understood as a system of citing works and authors, a system based on power and domination in which narratives of the orient come from wealthy, privileged westerners who speak for the orient.[xlvi] Said also states that cultural hegemony is what allows for the enduring idea of the orient, in this case, of China. This is further developed with the ideas that Europe and the U.S. is superior to all other cultures and ideas, and that European and U.S. superiority is reiterated over “oriental backwardness.” This is clearly evidenced in the work of the South China Mission.

One such example can be found among the correspondence of Harriet Noyes. In this

example, Harriet and her friend and coworker Miss E.M. Butler attend the funeral of one of their former students and teachers, A Yan. She says about the funeral, “It was such a forlorn sight… [A Yan’s] two little girls and an adopted daughter there just about of a daze and with white sack cloth sack in shams over their clothes and a piece of sack cloth over their heads! Looked too forlorn for anything…”[xlvii] In this letter, Harriet negatively describes the traditional funeral of one of her former teachers and students, showing disrespect through how much she pitied the funeral, one that aligned with the customs of the period in which it happened. Harriet’s pity implies that she feels that the funeral was backwards, and therefore lesser, aligning with Said’s description of a hegemonic air of western superiority.

In addition to the above, we must also examine how women played a role in the colonial project that was mission work. Although there were seemingly good reasons for women to become missionaries during the latter half of the 19th century (e.g., being able to establish a career in a time when many women were not able to do so, being able to enter the medical profession as a doctor, etc.), there were still major implications to their work. According to Cramer, “The identities of missionary women and of their relationships with women of other countries was predicated on whiteness and on excluding racial ‘others,’ or insisting on their conversion—a conversion that could be described as ‘whitening.’”[xlviii] Furthermore, Cramer argues that “observations of difference were coupled with the attitude missionary women held that women in other countries—indeed, entire countries—needed to be ‘whitened’ with the influence of the Christian Gospel.”[xlix] This perspective that missionary women, indeed most missionaries either men or women, that non-Christian, non-white people needed to be “whitened” with the Christian Gospel is truly just a continuance of the imperial/colonial project that was present in China during this period.

Conclusion

The PBFM and the South China Mission are of special historic significance—they operated together at a time during Chinese history when much transformation was going on as a result of colonial projects by various western nations (including France (Guangzhou), the U.S. (Guangzhou, Shanghai), Great Britain (Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Shanghai), Germany (Shandong Province, Guangzhou), and Portugal (Macau)) that they PBFM, through its South China Mission, was advancing the goals of the colonial projects occurring in Guangzhou at the time. Additionally, an historic organizational study has been lacking in the academic study of the PBFM and its South China Mission, as well as feminist and post-colonial perspectives on said organization. Through this paper I hope to have added to the body of work on the PBFM and the South China Mission in a way that has not yet been done.

[i] “Guide to the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A., Board of Foreign Missions, Department of Missionary Personnel Records,” Presbyterian Church (USA), archival finding aid, http://www.history.pcusa.org/collections/research-tools/guides-archival-collections/rg-360.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Noyes, Harriet. “Rev. Charles F. Preston—Dr. John G. Kerr, M.D.” Chapter in History of the South China Mission. (Shanghai: Presbyterian Mission Press, 1927). 17.

[viii] Speer, Robert. E. “The Missions of China.” In Presbyterian Foreign Missions. (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath School Work, 1901). 109.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid., 18.

[xii] Ibid., 18, 20-21.

[xiii] Ibid., 21-23.

[xiv] Noyes, Harriet. “Rev. Henry V. Noyes, D.D.” Chapter in History of the South China Mission. 24.

[xv] Ibid., 25.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Ibid., 26.

[xix] Noyes, Harriet. “Difficulties and Hindrances.” Chapter in History of the South China Mission. 32.

[xx] Noyes, Harriet. “The New School Building.” In Women’s Work for Woman. 2 no. 4 (Philadelphia: Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church, September 1872). 148.

[xxi] Happer, Dr. A.P. Letter. In Woman’s Work for Woman. 2 no. 1. (Philadelphia: Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church, March 1872). 7.

[xxii] “Difficulties and Hindrances.” 33.

[xxiii] Ibid., 34-5.

[xxiv] Ibid., 33.

[xxv] Ibid., 38.

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] Ibid.

[xxviii] Noyes, Harriet. “Progress and Encouragement.” In History of the South China Mission. 43.

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] Ibid., 63.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] Ibid.

[xxxiii] “Guide to the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A., Board of Foreign Missions, Department of Missionary Personnel Records,” Presbyterian Church (USA).

[xxxiv] Chen, Eugene. Eugene Chen to H.N. Noyes and E.M. Butler. Guangzhou, China, May 16, 1923. In The Noyes Collection, Box 5. The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[xxxv] Kaufmann, M. Alex. “HARRIET NOYES.” Photograph. (Wooster, Ohio: 2015). From The Noyes Collection digital files. The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[xxxvi] Kaufmann, M. Alex. “Noyes Main Stone #2.” Photograph. (Wooster, Ohio: 2015). From The Noyes Collection digital files. The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[xxxvii] Speer, Robert. E. “The Missions of China.” In Presbyterian Foreign Missions. 108.

[xxxviii] “History of the Organization and first years of our society prepared by its first secretary Mrs. O.N. Stoddard.” In Minutes 1890 Apr. to 1894 Mar. Minute book. In Women’s Foreign Missionary Society in Unprocessed Collections at The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[xxxix] Ianello, Katherine P. “Hierarchy.” In Decisions Without Hierarchy. (New York: Routledge, 1992). 19-20.

[xl] Ibid.

[xli] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Edward Noyes, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, February 9, 1871. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[xlii] al-Hajri, Hilal. “Through Evangelizing Eyes: American Missionaries to Oman.” In Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41 (2011). 123.

[xliii] Ibid., 124.

[xliv] Ibid., 125.

[xlv] Ibid.

[xlvi] Said, Edward. “Introduction” and “The Scope of Orientalism.” Chapters in Orientalism. (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, Ltd., 1978). Pp. 1-48.

[xlvii] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Lois Noyes. Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, September 11, 1882. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[xlviii] Cramer, Janet M. “White Womanhood and Religion: Colonial Discourse in the U.S. Women’s Missionary Press, 1869-1904.” In The Harvard Journal of Communications. 14 (2003). 214.

[xlix] Ibid.

The Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions (PBFM) was an organization under charge of the Presbyterian Church (USA) that commissioned missionaries and missions in foreign and domestic lands. One such mission that was under charge of the PBFM was the South China Mission, headquartered in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China (廣東省廣州市). This mission did a variety of work in Guangdong province, Hainan province, and other surrounding areas.

The focus of this study will be the South China Mission and the work it did, contextualizing it within the PBFM and other missions in China. This study will also focus on the decades ranging roughly from the 1840s to the 1890s, as the documents available to synthesize information for this study mostly concern this time, even though the South China Mission continued work for decades after the 1890s. The largest body of primary source materials for this study come from The College of Wooster’s Department of Special Collections—specifically its Noyes Collection, an archival collection of manuscript materials from the Noyes family, a prominent family within the South China Mission and the Presbyterian Church in Ohio, as well as the Missionary Alcove Collection, a special collection of published materials used for educating future missionaries during the late 19th and early 20th centuries when The College of Wooster trained missionaries to go abroad and do mission work. A body of secondary sources is also used for this research, including a finding aid for an archival collection belonging to the Presbyterian Church (USA) and secondary scholarship on mission work.

In this organizational study, I will examine the history of both the PBFM and its South China mission, describe its organizational structure and organizational values and culture, and provide feminist, post-colonial perspectives on the work done by the PBFM’s South China Mission.

History of The Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions (1837-1958)

The PBFM was organized in 1837 by the Presbyterian Church (USA), an action of the Old School of the Presbyterian Church.[i] At this time, the PBFM was not yet a legal entity, not being incorporated as such until 1862. During the years before 1862, the PBFM was a “benevolent society of the Presbyterian Church,” meaning it was a committee within the Church’s administration.[ii] The mission of the PBFM during this period was “to convey the Gospel ‘to whatever parts of the heathen and anti Christian world, the providence of God might enable the Society to extend its evangelical exertions.’”[iii] In 1862, the Board was finally incorporated as a legal entity within the state of New York.[iv] By the 1920s, the PBFM had missions located on the continents of Africa, Asia, South America, and North America.[v] The PBFM ended its tenure in 1958 when it was incorporated into the Commission on Ecumenical Mission and Relations under the United Presbyterian Church of the United States of America.[vi]

History of the South China Mission (1845-1890)

The first missionary to be commissioned for work in South China, was Dr. Andrew P. Happer, who arrived in China with his wife in approximately 1845 in Macau, opening a boarding school for boys in the same year.[vii],[viii] In 1847, Dr. Happer and his wife moved their work to Guangzhou, where they stayed for many years.[ix] This marks the beginning of the South China mission under control of the PBFM. Following opening the boarding school in Macau, Dr. Happer also taught English in a Chinese Imperial Government school, as well as opened a hospital and dispensary in 1851 in Guangzhou.[x] The mission force, after nearly ten years of doing work alone under the PBFM, grew to five with the arrival of Dr. John G. Kerr, his wife, and Mr. Preston in 1854.[xi] At this time, Mr. Preston began street preaching, and Dr. Kerr immediately took over the hospital that had been run by Dr. Happer previously.[xii] The mission did not grow more until 1860, when Rev. Condit and his wife arrived in China, and in 1863, Rev. Folsom and his wife arrived. It was originally intended for these new missionaries to set up a sister mission in Foshan, Guangdong (廣東省佛山市, 12 miles from Guangzhou, then called Fat Shaan by English speakers), however, this never came to fruition, although other Christian denominations did set up missions in Foshan.[xiii]

A new era of the South China mission began in 1866 with the arrival of Dr. Henry Varnum Noyes with his wife. These missionaries were the last of the South China Mission to arrive in China by sailboat, as steamers commenced running lines between the United States and Japan, as well as Hong Kong in 1867.[xiv] I mark his arrival as a new era of mission work by the South China mission due to Dr. Noyes’ increased attempts to go further inland to do mission work, something that had been extremely limited by the Chinese Imperial Government for many years beforehand, and still was at the time.[xv] However, Dr. Noyes still attempted to go further inland from Guangzhou, a city that sits on the Pearl River Delta, and would land his boat (as most travel inland was by boat at this time) wherever he was allowed. However, this did prove dangerous at times. According to Harriet Noyes, there was at one point a group of ninety-six villages that vowed to “kill anyone who should ever dare to bring a foreigner to one of their villages.”[xvi] Although there were these dangers, Dr. Noyes still would attempt to street preach inland as funds for education endeavors were not available at the time.[xvii] Additionally, in 1867, two mission homes were constructed for the mission, the first to be built according to “western ideas” by the mission, and possibly in all of Guangzhou.[xviii]

The mission force continued to grow, and in 1868, following the death of Dr. Noyes’ wife, his sister Harriet, accompanied by Dr. and Mrs. Kerr who had been on furlough, arrived in Guangzhou. Harriet would prove to be a major boon to the work of the South China Mission, starting off right away opening a day school soon after her arrival. Following Harriet’s arrival and the return of the Kerrs, the mission force doubled in 1870 from six missionaries to twelve. Following the growth of the South China Mission, Harriet Noyes established one of the first boarding schools for women and girls in Guangdong, and possibly all of China, in 1872.[xix],[xx] There had been earlier attempts by Dr. Happer’s wife to do so, but those attempts went unfinished due to sickness in the first attempt, and her death in the second attempt.[xxi] Three years following the opening of the boarding school for women and girls, the True Light Seminary (真光書院, still running now as the True Light Middle Schools of Hong Kong and Kowloon with other sister schools) opened, with a graduating class of nine girls following their three years of study at the Seminary.[xxii]

Following the opening of the True Light Seminary (TLS), in 1873, Harriet had ensured the training of six women to be bible women, Chinese women who went home-to-home in order to spread the word of the Presbyterian Gospel.[xxiii] Continuing work in education, which Harriet deemed to be “the most practicable and satisfactory way of reaching the women and children,”[xxiv] Dr. Noyes opened a boarding school for boys in 1878.[xxv] The mission continued to grow and grow as years went on. By the end of 1879, the mission had 12 missionaries from America, 15 assistant men, 7 bible women, 15 teachers, and 545 students in the South China Mission’s schools.[xxvi] In the following year, 1880, the Mission controlled $10,604 in expenditures——$3600 for 4 married missionaries and their wives, $1800 for 4 unmarried missionaries, $1,140 for 14 assistant men, $294 for 7 bible women, $1,280 for 2 boarding schools, $1,200 for 14 day schools, $500 for 5 language teachers, and $790 for miscellaneous costs.[xxvii] It is clear through these numbers the amount that the South China Mission grew since its beginnings with Dr. Happer in 1845.

However, the mission continued to grow greatly. Happening between 1880 and 1882, the mission received 18 new missionaries—more than doubling the amount of Americans working for the mission.[xxviii] Also, from 1880 to 1885, five new Presbyterian churches in addition to the two that already existed in Guangzhou, and the number of “outstations” in the surrounding areas of Guangzhou grew to twenty-four.[xxix] The number of students also continued to grow, with 636 students in boarding schools and day schools by the end of the 1880s.[xxx] The number of patients being seen at the hospital was also staggering for the small number of missionaries heading up the work—there were 39,500 patients seen in 1887, with over 4,000 surgeries being performed.[xxxi] Additionally, eighteen Chinese students were training to be doctors, with five of them being women.[xxxii]

The work of the missionaries and all those who helped them did not cease at the end of the 1880s, and actually continued until 1946.[xxxiii] It is likely that the mission ceased work at this time due to the civil war occurring between the nationalist Republic of China and communist fighters. I end my study of the mission’s history at the end of the 1880s because further study would be beyond the scope of this project. Harriet Noyes continued her work in China until 1923, just months before her January, 1924 death;[xxxiv][xxxv] Henry Noyes continued his work in China until his death in 1926;[xxxvi] Dr. Happer continued his work until his death in 1894.[xxxvii]

Organizational Structure and Values of the PBFM and South China Mission

The structure of the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions and its South China mission is quite interesting, and needs to be looked at in the broader context of the Presbyterian Church of the United States of America at the time. The following diagram can help us better understand the structure of the PBFM and its South China mission, as well as how money was distributed to various parts of the organization and where it was sourced. [see image 3.4 at the bottom of this page]

We can trace much of the funding for the South China Mission and the PBFM itself to local churches and Foreign Missionary Societies their parishioners created. Churches could ask parishioners for donations on the behalf of missionaries, and Foreign Missionary Societies would often do different fundraising activities like sewing and sewing quilts to holding banquets.[xxxviii] Funds could be sent from local churches to the Presbyterian Church (USA)(PCUSA), which could then be sent to the PBFM. Funds could also be sent from the local churches or the Foreign Missionary Societies (FMS) directly to the mission, or from the FMS to the PBFM. Often, the PBFM would need to approve major spending, so it is likely the PBFM collected much of the money that was sent to the individual missions.

As it may be clear, the PBFM and its South China Mission do not neatly fit into a certain type of organizational structure. However, according to Kathleen Ianello’s definitions of decentralized and fragmented organizations, the PBFM and South China Mission can be described as a mix between a decentralized organization and a fragmented organization. A decentralized organization, according to Ianello, is one with a bottom-up organizational structure, where some of the major decisions and most routine decisions are made by the lower parts of the organization, i.e., the South China Mission, with the higher parts of the hierarchy, i.e., the PBFM, still make most of the major decisions.[xxxix] However, in fragmented organizations, most of the major decisions are made by the lower parts of the hierarchy, and the upper parts of the hierarchy no longer have much control.[xl] I deem the PBFM and the South China Mission a mix between these two types of organizational structures because the South China Mission would make some major decisions, where the PBFM would make some as well. For instance, the PBFM would approve of a budget for a school for the South China Mission, and the South China Mission would decide how it would be designed architecturally.[xli] However, I also categorize it as fragmented due to the number of major decisions made by the South China Mission.

Relying on archival documents, it is difficult to determine the official organizational values of the PBFM and South China mission as most of the manuscript material is personal correspondence from members of the South China Mission, however, as discussed above, a mission statement for the PBFM itself is available. The mission of the PBFM during this period was “to convey the Gospel ‘to whatever parts of the heathen and anti Christian world, the providence of God might enable the Society to extend its evangelical exertions.’” Here, it is clear that the main motivation for creating these missions across the globe is obviously to evangelize non-Christians. However, the wording of the mission can tell us more about the values of the organization itself. The use of the word “heathen” in the mission for the PBFM signifies an air of superiority and condescension towards non-Christians. Additionally, the use of “anti Christian” reflects the frequent self-victimization some Christian denominations utilize for sympathy. Finally, “the providence of God,” signified how the PBFM views its actions as sanctioned by God himself. Although much cannot be derived from this mission statement alone, there is some valuable information contained within it.

Post-Colonial, Feminist Perspectives

The motivations for mission work were not always well-intentioned, or if they were, they were very often shrouded in attitudes of racism, ethnocentrism, and religious superiority. These attitudes need to be examined to understand the implications of mission work. Although much of the work that was done by the South China Mission can be portrayed easily in a positive light, specifically the educational and medical aspects of the mission work, there was still often an air of the attitudes discussed above by the missionaries themselves.

According to al-Hajri, “’most missionaries were primarily concerned with evangelizing the world first and providing humanitarian aid to foreign people second.’”[xlii] Additionally, al-Hajri argues that “all non-Christians needed to be educated so they could read the Bible and gain the knowledge of Christian beliefs and values.” These two statements about the primary motivations of missionaries in foreign lands show that the purpose behind mission work was never to provide aid to the people where missionaries colonized, but rather to evangelize the people of these nations, and if need be, to provide aid to entice them to evangelize. al-Hajri also specifically addresses the topic of education in their piece: “Education was also emphasized by American Missionaries from the very beginning. If preaching the Gospel was necessary, it was also necessary to spread education so that the Bible could be read and understood.”[xliii]

In addition to the above, the work of missionaries can also be understood in terms of violence. “Apart from praising the gentle ‘gospel of love,’ American missionaries described evangelization, very obviously in many instances, as war… American missionaries… frequently used… words such as ‘war’ and ‘occupy’ in their journals and reports.”[xliv] Furthermore, al-Hajri also states that, “The connection between being martyrs and spreading Christianity indicates the missionaries viewed the work they were performing as a war in which they must win over other religious groups. Any interactions that happened with non-Christians were interactions with the enemy.”[xlv]

We must also understand the mission work being done in the South China Mission as orientalist in nature. Orientalism, according to Edward Said, who coined the term, should be understood as a system of citing works and authors, a system based on power and domination in which narratives of the orient come from wealthy, privileged westerners who speak for the orient.[xlvi] Said also states that cultural hegemony is what allows for the enduring idea of the orient, in this case, of China. This is further developed with the ideas that Europe and the U.S. is superior to all other cultures and ideas, and that European and U.S. superiority is reiterated over “oriental backwardness.” This is clearly evidenced in the work of the South China Mission.

One such example can be found among the correspondence of Harriet Noyes. In this

example, Harriet and her friend and coworker Miss E.M. Butler attend the funeral of one of their former students and teachers, A Yan. She says about the funeral, “It was such a forlorn sight… [A Yan’s] two little girls and an adopted daughter there just about of a daze and with white sack cloth sack in shams over their clothes and a piece of sack cloth over their heads! Looked too forlorn for anything…”[xlvii] In this letter, Harriet negatively describes the traditional funeral of one of her former teachers and students, showing disrespect through how much she pitied the funeral, one that aligned with the customs of the period in which it happened. Harriet’s pity implies that she feels that the funeral was backwards, and therefore lesser, aligning with Said’s description of a hegemonic air of western superiority.

In addition to the above, we must also examine how women played a role in the colonial project that was mission work. Although there were seemingly good reasons for women to become missionaries during the latter half of the 19th century (e.g., being able to establish a career in a time when many women were not able to do so, being able to enter the medical profession as a doctor, etc.), there were still major implications to their work. According to Cramer, “The identities of missionary women and of their relationships with women of other countries was predicated on whiteness and on excluding racial ‘others,’ or insisting on their conversion—a conversion that could be described as ‘whitening.’”[xlviii] Furthermore, Cramer argues that “observations of difference were coupled with the attitude missionary women held that women in other countries—indeed, entire countries—needed to be ‘whitened’ with the influence of the Christian Gospel.”[xlix] This perspective that missionary women, indeed most missionaries either men or women, that non-Christian, non-white people needed to be “whitened” with the Christian Gospel is truly just a continuance of the imperial/colonial project that was present in China during this period.

Conclusion

The PBFM and the South China Mission are of special historic significance—they operated together at a time during Chinese history when much transformation was going on as a result of colonial projects by various western nations (including France (Guangzhou), the U.S. (Guangzhou, Shanghai), Great Britain (Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Shanghai), Germany (Shandong Province, Guangzhou), and Portugal (Macau)) that they PBFM, through its South China Mission, was advancing the goals of the colonial projects occurring in Guangzhou at the time. Additionally, an historic organizational study has been lacking in the academic study of the PBFM and its South China Mission, as well as feminist and post-colonial perspectives on said organization. Through this paper I hope to have added to the body of work on the PBFM and the South China Mission in a way that has not yet been done.

[i] “Guide to the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A., Board of Foreign Missions, Department of Missionary Personnel Records,” Presbyterian Church (USA), archival finding aid, http://www.history.pcusa.org/collections/research-tools/guides-archival-collections/rg-360.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Noyes, Harriet. “Rev. Charles F. Preston—Dr. John G. Kerr, M.D.” Chapter in History of the South China Mission. (Shanghai: Presbyterian Mission Press, 1927). 17.

[viii] Speer, Robert. E. “The Missions of China.” In Presbyterian Foreign Missions. (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath School Work, 1901). 109.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid., 18.

[xii] Ibid., 18, 20-21.

[xiii] Ibid., 21-23.

[xiv] Noyes, Harriet. “Rev. Henry V. Noyes, D.D.” Chapter in History of the South China Mission. 24.

[xv] Ibid., 25.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Ibid., 26.

[xix] Noyes, Harriet. “Difficulties and Hindrances.” Chapter in History of the South China Mission. 32.

[xx] Noyes, Harriet. “The New School Building.” In Women’s Work for Woman. 2 no. 4 (Philadelphia: Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church, September 1872). 148.

[xxi] Happer, Dr. A.P. Letter. In Woman’s Work for Woman. 2 no. 1. (Philadelphia: Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church, March 1872). 7.

[xxii] “Difficulties and Hindrances.” 33.

[xxiii] Ibid., 34-5.

[xxiv] Ibid., 33.

[xxv] Ibid., 38.

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] Ibid.

[xxviii] Noyes, Harriet. “Progress and Encouragement.” In History of the South China Mission. 43.

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] Ibid., 63.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] Ibid.

[xxxiii] “Guide to the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A., Board of Foreign Missions, Department of Missionary Personnel Records,” Presbyterian Church (USA).

[xxxiv] Chen, Eugene. Eugene Chen to H.N. Noyes and E.M. Butler. Guangzhou, China, May 16, 1923. In The Noyes Collection, Box 5. The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[xxxv] Kaufmann, M. Alex. “HARRIET NOYES.” Photograph. (Wooster, Ohio: 2015). From The Noyes Collection digital files. The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[xxxvi] Kaufmann, M. Alex. “Noyes Main Stone #2.” Photograph. (Wooster, Ohio: 2015). From The Noyes Collection digital files. The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[xxxvii] Speer, Robert. E. “The Missions of China.” In Presbyterian Foreign Missions. 108.

[xxxviii] “History of the Organization and first years of our society prepared by its first secretary Mrs. O.N. Stoddard.” In Minutes 1890 Apr. to 1894 Mar. Minute book. In Women’s Foreign Missionary Society in Unprocessed Collections at The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[xxxix] Ianello, Katherine P. “Hierarchy.” In Decisions Without Hierarchy. (New York: Routledge, 1992). 19-20.

[xl] Ibid.

[xli] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Edward Noyes, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, February 9, 1871. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[xlii] al-Hajri, Hilal. “Through Evangelizing Eyes: American Missionaries to Oman.” In Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41 (2011). 123.

[xliii] Ibid., 124.

[xliv] Ibid., 125.

[xlv] Ibid.

[xlvi] Said, Edward. “Introduction” and “The Scope of Orientalism.” Chapters in Orientalism. (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, Ltd., 1978). Pp. 1-48.

[xlvii] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Lois Noyes. Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, September 11, 1882. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[xlviii] Cramer, Janet M. “White Womanhood and Religion: Colonial Discourse in the U.S. Women’s Missionary Press, 1869-1904.” In The Harvard Journal of Communications. 14 (2003). 214.

[xlix] Ibid.