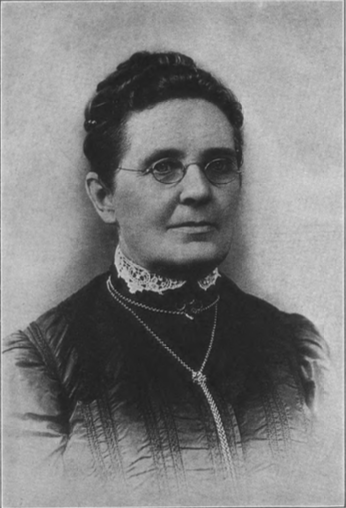

Harriet Noyes

A Biography

Introduction

Harriet Newell Noyes (1844-1924),[1] born in Seville, Ohio, a small village approximately 40 miles south of Cleveland, Ohio, was a missionary for the Presbyterian Church’s Board of Foreign Missions for nearly 56 years[2] in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, China (廣東省廣州市). As a missionary, Harriet played a major role in establishing Presbyterian day schools and boarding schools in and around Guangzhou, China, then referred to by English-speakers as Canton, Kwangtung province (a difference in Romanization styles—Guangzhou, Guangdong is from the Pinyin Romanization style, whereas Canton, Kwangtung is from the antiquated Chinese postal Romanization style). In this paper, I will be recounting various events of Harriet’s life, as well as offering a critique of her work as a cultural imperialist from a post-colonial perspective. All research for this paper has been conducted over a period of three years, commencing with my assignment to process the Noyes Collection[3] at The College of Wooster under the supervision of Denise Monbarren, Special Collections Librarian for The College of Wooster. Research was conducted over these three years as I processed the collection, as well as after leaving Wooster to attend The Ohio State University. Most information for this paper comes from primary source documents and photographs contained in the Noyes Collection, however, a number of other sources are used as well.

Harriet Newell Noyes: Missionary to China (1868-1923)

Harriet Newell Noyes, named after Harriet Newell, an early missionary to India and Burma, was born in Seville, Ohio, daughter of the small village’s first Presbyterian Minister, Varnum Noyes. It can be gleaned from the materials of the Noyes Collection that Harriet led a relatively normal life for that of a white, upper-middle class child of a Presbyterian Minister in rural Ohio. Various letters from the collection exhibit Harriet reminiscing to her siblings positive memories of growing up on a farm—riding horses and playing with the family dog. Once Harriet grew up, she believed strongly in serving the word of God, and did so through service to her country. Harriet spent time during the Civil War in some capacity helping the Union army, either as a cook or as a nurse, and also spent some time in a hospital during the war, either as a patient or as a nurse.[4]

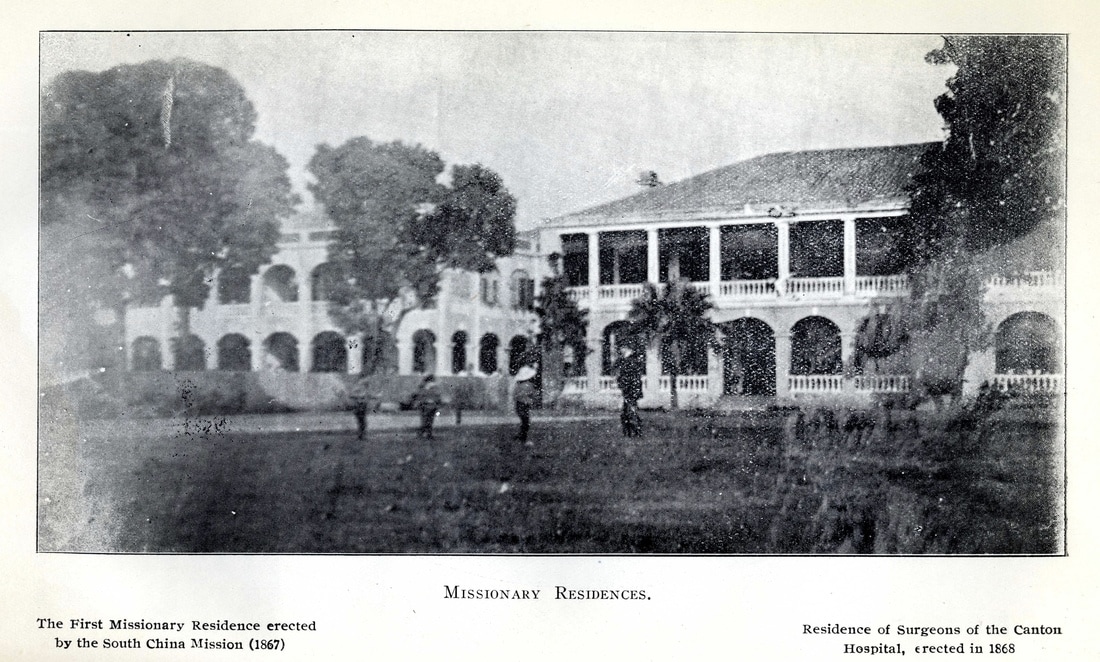

Following her service in the Civil War, Harriet decided to spend the rest of her life dedicated to what she saw as the work of God, and applied to be a missionary with the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions (PBFM). Harriet was accepted by the board, and at the end of 1867 was sent on a steamer to be a missionary for the PBFM’s South China Mission in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, China. Harriet arrived in January 1868 on a steamer,[5] having travelled with about eight hundred other people,[6] and immediately began learning Cantonese,[7] the language spoken in Guangzhou and its surrounding areas. It is unclear what mission work Harriet engaged in when she first arrived, if any. It is possible that she just spent her time helping her brother Henry, who had arrived with his wife in 1866 who tragically died of disease in 1867,[8] and learning Cantonese with Chinese teachers.

By 1869, however, Harriet had commenced her work in education. Harriet taught in day schools.[9] As time went on, Harriet began to run more day schools in Guangzhou and its surrounding areas. However, Harriet’s biggest accomplishment was the opening of the True Light Seminary in 1872. Harriet recalls the opening of the True Light Seminary (TLS) in her History of the South China Mission:

On the sixteenth of June, 1872, the True Light Seminary was opened in charge of Miss Harriet N. Noyes. "At the first meeting held in the little school chapel there were only sixteen present, Miss Lillie Happer, Miss Harriet N. Noyes, a few Chinese women and girls and several little children, all that could then be induced to come to such a meeting. It was still the day of small things, and especially so in the line of educational advantages for girls and women."[10]

After this, Harriet also recalls how difficult it was to secure pupils at this boarding schools, saying that even with free tuition, room and board, clothing, and “all incidental expenses,” she was still only able to enroll four students in the TLS’s first year.[11] This comes of no surprise, however, for anti-foreigner sentiments in Guangzhou and its surrounding areas were very strong at the time.

In fact, in her History of the South China Mission, Harriet tells of an area of ninety-six villages that banded together to pledge to kill anyone who may bring a foreigner into their area.[12] Although this may sound possible sensationalist, following the events of the Opium Wars, anti-foreigner sentiments were extremely high, and the Chinese imperial government thoroughly restricted the movement of foreigners inland.

The opening of TLS was also a landmark for women and girls’ education in Guangdong, and likely all of China. TLS was one of the first boarding schools for women and girls, and has Harriet has been acclaimed for her work by Dr. Sun Yat-Sen, revolutionary and founder of the Republic of China[13] as well as more recent organizations, including the All-China Women’s Federation.[14] Although there are many implications of her activist work that can lead to serious critiques of Harriet and her work, the recognition that she has received in the past and in the present should most definitely be noted.

Following the opening of TLS, Harriet’s work continued in education, keeping busy with running TLS and many day schools in Guangzhou and in surrounding villages. Harriet often accompanied her brother in trips inland, after eventual easing of restrictions from the imperial government, to help preach the word of God to what she saw as a “heathen nation.” In 1876, Harriet travelled home for a furlough with her brother Henry, going by way of the Mediterranean, visiting the Holy Land on their way.[15]

After their furlough, Harriet continued her work with education—administering her school, overseeing the education of girls, women, and boys. Harriet’s correspondence to her family dwindles in the 1880s, mostly telling her family about anti-foreigner violence and threats of violence, and some major events in Chinese history. However, these will not be focused on at this time. As noted above, Harriet and her close friend and coworker, E.M. Butler, were recognized for their work by Dr. Sun Yat-sen, by way of his secretary Eugene Chen, “on the eve of [their] departure for America.” This acknowledgement in itself is of great historical value, and shows the positive impact that Harriet had on education in China.

Harriet Noyes: Cultural Imperialist

Although Harriet did receive acclaim for her work as a missionary establishing schools throughout Guangzhou and its surrounding areas, her work should not go without critique. As a white, upper-middle class woman, Harriet enters China with specific presuppositions and a specific agenda: that China is a “heathen land” that is lesser than western nations because it has not been Christianized, and that it is her duty to help Christianize the people of China so they do not spend eternity in Hell. Harriet clearly operated under a notion of white-saviorhood. It should also be noted that Harriet did not go into this culturally imperialist endeavor by herself—the Presbyterian Church also played a major role in influencing those who wanted to become missionaries.

To address the role of the church in this cultural imperialism, I turn to the work of Janet M. Cramer. Cramer states that “Churches established a brand of mission work specifically for single women to reach women in other countries. Thus, the [missionary] movement gave a kind of divine sanction to a woman’s transgression of the private sphere…”[16] This means that churches intentionally broke the tie that women had to the home at this time in order to perpetuate its interventionist and white-saviorhood stances on Christianizing non-Christian Nations. Cramer argues that white women, like Harriet Noyes, were “implicated in the colonial process.”[17] However, I argue, as does Cramer, that white women were not passive agents in this implication within the colonial process. Rather, their racist attitudes towards non-Christian peoples played well with churches’ sanctioning of single women becoming missionaries; “Missionary women exalted themselves in their ‘woman’s work for woman’ in their religious superiority (both compared to women in other countries and to men in the missionary effort), in their expressions of true love for humanity and God as expressed through altruism…”[18]

To focus on Harriet as an agent of cultural imperialism or colonialism, we should focus on how missionaries like Harriet considered conversion to Christianity to be a process of “whitening.” According to Cramer, “The identities of missionary women and of their relationship with women of other countries were predicated on Whiteness and on excluding racial ‘others,’ or insisting on their conversion—a conversion that can be described as ‘Whitening.’”[19] Furthermore, Cramer argues that “…observations of difference were coupled with the attitude missionary women held that women in other countries… needed to be ‘Whitened’ with the influence of the Christian gospel.”[20] Harriet’s similar motivations can be found in a letter from soon after her arrival in China: “…the Chinese have a business mentality and understand economy perfectly. If they were Christian there would be nothing left to teach them…”[21] This is evidence, along with many other letters that condemn Chinese religious and cultural practices, that Harriet too bought into the racist ideals that non-Christian non-white peoples of the world needed to be “whitened” with Christianity.

Conclusion

Harriet Noyes is a missionary in China that has received almost no scholastic attention—she has merely been mentioned in footnotes or her works cited by Presbyterian historians, but no work has focused solely on her. Harriet’s role as a missionary in Guangzhou during a period of rapid transformation in China needs to be understood with greater depth, especially for her major impact on women and girls’ education in Guangzhou. According to Eugene Chen in his letter to Harriet and E.M. Butler, Harriet was responsible for training nearly 6,000 women and girls, just from those enrolled at TLS. Other sources, including Eileen Cheng’s article, state that Harriet was responsible for establishing the first generation of professional women in Guangzhou. Although Harriet and her work need recognition to some degree, it should also be kept in mind that her work should also receive some critique for its culturally imperialist implications.

Harriet Newell Noyes (1844-1924),[1] born in Seville, Ohio, a small village approximately 40 miles south of Cleveland, Ohio, was a missionary for the Presbyterian Church’s Board of Foreign Missions for nearly 56 years[2] in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, China (廣東省廣州市). As a missionary, Harriet played a major role in establishing Presbyterian day schools and boarding schools in and around Guangzhou, China, then referred to by English-speakers as Canton, Kwangtung province (a difference in Romanization styles—Guangzhou, Guangdong is from the Pinyin Romanization style, whereas Canton, Kwangtung is from the antiquated Chinese postal Romanization style). In this paper, I will be recounting various events of Harriet’s life, as well as offering a critique of her work as a cultural imperialist from a post-colonial perspective. All research for this paper has been conducted over a period of three years, commencing with my assignment to process the Noyes Collection[3] at The College of Wooster under the supervision of Denise Monbarren, Special Collections Librarian for The College of Wooster. Research was conducted over these three years as I processed the collection, as well as after leaving Wooster to attend The Ohio State University. Most information for this paper comes from primary source documents and photographs contained in the Noyes Collection, however, a number of other sources are used as well.

Harriet Newell Noyes: Missionary to China (1868-1923)

Harriet Newell Noyes, named after Harriet Newell, an early missionary to India and Burma, was born in Seville, Ohio, daughter of the small village’s first Presbyterian Minister, Varnum Noyes. It can be gleaned from the materials of the Noyes Collection that Harriet led a relatively normal life for that of a white, upper-middle class child of a Presbyterian Minister in rural Ohio. Various letters from the collection exhibit Harriet reminiscing to her siblings positive memories of growing up on a farm—riding horses and playing with the family dog. Once Harriet grew up, she believed strongly in serving the word of God, and did so through service to her country. Harriet spent time during the Civil War in some capacity helping the Union army, either as a cook or as a nurse, and also spent some time in a hospital during the war, either as a patient or as a nurse.[4]

Following her service in the Civil War, Harriet decided to spend the rest of her life dedicated to what she saw as the work of God, and applied to be a missionary with the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions (PBFM). Harriet was accepted by the board, and at the end of 1867 was sent on a steamer to be a missionary for the PBFM’s South China Mission in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, China. Harriet arrived in January 1868 on a steamer,[5] having travelled with about eight hundred other people,[6] and immediately began learning Cantonese,[7] the language spoken in Guangzhou and its surrounding areas. It is unclear what mission work Harriet engaged in when she first arrived, if any. It is possible that she just spent her time helping her brother Henry, who had arrived with his wife in 1866 who tragically died of disease in 1867,[8] and learning Cantonese with Chinese teachers.

By 1869, however, Harriet had commenced her work in education. Harriet taught in day schools.[9] As time went on, Harriet began to run more day schools in Guangzhou and its surrounding areas. However, Harriet’s biggest accomplishment was the opening of the True Light Seminary in 1872. Harriet recalls the opening of the True Light Seminary (TLS) in her History of the South China Mission:

On the sixteenth of June, 1872, the True Light Seminary was opened in charge of Miss Harriet N. Noyes. "At the first meeting held in the little school chapel there were only sixteen present, Miss Lillie Happer, Miss Harriet N. Noyes, a few Chinese women and girls and several little children, all that could then be induced to come to such a meeting. It was still the day of small things, and especially so in the line of educational advantages for girls and women."[10]

After this, Harriet also recalls how difficult it was to secure pupils at this boarding schools, saying that even with free tuition, room and board, clothing, and “all incidental expenses,” she was still only able to enroll four students in the TLS’s first year.[11] This comes of no surprise, however, for anti-foreigner sentiments in Guangzhou and its surrounding areas were very strong at the time.

In fact, in her History of the South China Mission, Harriet tells of an area of ninety-six villages that banded together to pledge to kill anyone who may bring a foreigner into their area.[12] Although this may sound possible sensationalist, following the events of the Opium Wars, anti-foreigner sentiments were extremely high, and the Chinese imperial government thoroughly restricted the movement of foreigners inland.

The opening of TLS was also a landmark for women and girls’ education in Guangdong, and likely all of China. TLS was one of the first boarding schools for women and girls, and has Harriet has been acclaimed for her work by Dr. Sun Yat-Sen, revolutionary and founder of the Republic of China[13] as well as more recent organizations, including the All-China Women’s Federation.[14] Although there are many implications of her activist work that can lead to serious critiques of Harriet and her work, the recognition that she has received in the past and in the present should most definitely be noted.

Following the opening of TLS, Harriet’s work continued in education, keeping busy with running TLS and many day schools in Guangzhou and in surrounding villages. Harriet often accompanied her brother in trips inland, after eventual easing of restrictions from the imperial government, to help preach the word of God to what she saw as a “heathen nation.” In 1876, Harriet travelled home for a furlough with her brother Henry, going by way of the Mediterranean, visiting the Holy Land on their way.[15]

After their furlough, Harriet continued her work with education—administering her school, overseeing the education of girls, women, and boys. Harriet’s correspondence to her family dwindles in the 1880s, mostly telling her family about anti-foreigner violence and threats of violence, and some major events in Chinese history. However, these will not be focused on at this time. As noted above, Harriet and her close friend and coworker, E.M. Butler, were recognized for their work by Dr. Sun Yat-sen, by way of his secretary Eugene Chen, “on the eve of [their] departure for America.” This acknowledgement in itself is of great historical value, and shows the positive impact that Harriet had on education in China.

Harriet Noyes: Cultural Imperialist

Although Harriet did receive acclaim for her work as a missionary establishing schools throughout Guangzhou and its surrounding areas, her work should not go without critique. As a white, upper-middle class woman, Harriet enters China with specific presuppositions and a specific agenda: that China is a “heathen land” that is lesser than western nations because it has not been Christianized, and that it is her duty to help Christianize the people of China so they do not spend eternity in Hell. Harriet clearly operated under a notion of white-saviorhood. It should also be noted that Harriet did not go into this culturally imperialist endeavor by herself—the Presbyterian Church also played a major role in influencing those who wanted to become missionaries.

To address the role of the church in this cultural imperialism, I turn to the work of Janet M. Cramer. Cramer states that “Churches established a brand of mission work specifically for single women to reach women in other countries. Thus, the [missionary] movement gave a kind of divine sanction to a woman’s transgression of the private sphere…”[16] This means that churches intentionally broke the tie that women had to the home at this time in order to perpetuate its interventionist and white-saviorhood stances on Christianizing non-Christian Nations. Cramer argues that white women, like Harriet Noyes, were “implicated in the colonial process.”[17] However, I argue, as does Cramer, that white women were not passive agents in this implication within the colonial process. Rather, their racist attitudes towards non-Christian peoples played well with churches’ sanctioning of single women becoming missionaries; “Missionary women exalted themselves in their ‘woman’s work for woman’ in their religious superiority (both compared to women in other countries and to men in the missionary effort), in their expressions of true love for humanity and God as expressed through altruism…”[18]

To focus on Harriet as an agent of cultural imperialism or colonialism, we should focus on how missionaries like Harriet considered conversion to Christianity to be a process of “whitening.” According to Cramer, “The identities of missionary women and of their relationship with women of other countries were predicated on Whiteness and on excluding racial ‘others,’ or insisting on their conversion—a conversion that can be described as ‘Whitening.’”[19] Furthermore, Cramer argues that “…observations of difference were coupled with the attitude missionary women held that women in other countries… needed to be ‘Whitened’ with the influence of the Christian gospel.”[20] Harriet’s similar motivations can be found in a letter from soon after her arrival in China: “…the Chinese have a business mentality and understand economy perfectly. If they were Christian there would be nothing left to teach them…”[21] This is evidence, along with many other letters that condemn Chinese religious and cultural practices, that Harriet too bought into the racist ideals that non-Christian non-white peoples of the world needed to be “whitened” with Christianity.

Conclusion

Harriet Noyes is a missionary in China that has received almost no scholastic attention—she has merely been mentioned in footnotes or her works cited by Presbyterian historians, but no work has focused solely on her. Harriet’s role as a missionary in Guangzhou during a period of rapid transformation in China needs to be understood with greater depth, especially for her major impact on women and girls’ education in Guangzhou. According to Eugene Chen in his letter to Harriet and E.M. Butler, Harriet was responsible for training nearly 6,000 women and girls, just from those enrolled at TLS. Other sources, including Eileen Cheng’s article, state that Harriet was responsible for establishing the first generation of professional women in Guangzhou. Although Harriet and her work need recognition to some degree, it should also be kept in mind that her work should also receive some critique for its culturally imperialist implications.

Citations

[1] Kaufmann, M. Alex. “HARRIET NOYES.” Photograph. (Wooster, Ohio: 2015). From The Noyes Family Graves in The Noyes Collection. The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The Noyes Collection is a collection containing mostly correspondence between Harriet and her other family members. Other materials in this collection include posters, journals, photographs, and other manuscript materials. This collection was given to The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections from the Noyes family due to the family’s connection with The College—Emily Noyes, Harriet’s younger sister, was The College’s first woman graduate (class of 1874).

[4] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Edward Noyes, Guangzhou, China, December 11, 1868. In The Noyes Collection, box 1. The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[5] Steamers had just began running between the United States and China 1867, earlier missionaries arrived on sailboats.

[6] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Varnum Noyes, Guangzhou, China, November 8, 1867. In The Noyes Collection, box 1. The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio. It is likely that this trip took her to Yokohama, Japan, for The History of the South China Mission by Harriet Noyes reports that she arrived in Guangzhou in January of 1868.

[7] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Emily Noyes, Guangzhou, China, May 4, 1868. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[8] Noyes, Harriet. “Rev. Henry Varnum Noyes, D.D.” In The History of the South China Mission. (Shanghai: Presbyterian Mission Press, 1927). 24.

[9] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Mary Noyes, Guangzhou, China, February 15, 1869. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[10] Noyes, Harriet. “Difficulties and Hindrances.” In The History of the South China Mission. (Shanghai: Presbyterian Mission Press, 1927). 32.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Noyes, Harriet. “Rev. Henry Varnum Noyes, D.D.” 25.

[13] Chen, Eugene. Eugene Chen to Harriet Noyes and E. Butler. Guangzhou, China, May 16, 1923. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[14] Cheng, Eileen. “Harriet Newell Noyes: Foreign Pioneer of Women’s Education in Guangdong.” For Women of China, website. All-China Women’s Federation (February 4, 2015). http://www.womenofchina.cn/womenofchina/html1/people/history/1502/159-1.htm.

[15] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to various family members, various locations, 1876. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[16] Cramer, Janet M. “White Womanhood and Religion: Colonial Discourse in the U.S. Women’s Missionary Press, 1869-1914.” In The Harvard Journal of Communication. 14 (2003). 210.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid., 213.

[19] Ibid., 214.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Sarah Noyes, Guangzhou, China, June 3, 1868. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[1] Kaufmann, M. Alex. “HARRIET NOYES.” Photograph. (Wooster, Ohio: 2015). From The Noyes Family Graves in The Noyes Collection. The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The Noyes Collection is a collection containing mostly correspondence between Harriet and her other family members. Other materials in this collection include posters, journals, photographs, and other manuscript materials. This collection was given to The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections from the Noyes family due to the family’s connection with The College—Emily Noyes, Harriet’s younger sister, was The College’s first woman graduate (class of 1874).

[4] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Edward Noyes, Guangzhou, China, December 11, 1868. In The Noyes Collection, box 1. The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[5] Steamers had just began running between the United States and China 1867, earlier missionaries arrived on sailboats.

[6] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Varnum Noyes, Guangzhou, China, November 8, 1867. In The Noyes Collection, box 1. The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio. It is likely that this trip took her to Yokohama, Japan, for The History of the South China Mission by Harriet Noyes reports that she arrived in Guangzhou in January of 1868.

[7] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Emily Noyes, Guangzhou, China, May 4, 1868. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[8] Noyes, Harriet. “Rev. Henry Varnum Noyes, D.D.” In The History of the South China Mission. (Shanghai: Presbyterian Mission Press, 1927). 24.

[9] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Mary Noyes, Guangzhou, China, February 15, 1869. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[10] Noyes, Harriet. “Difficulties and Hindrances.” In The History of the South China Mission. (Shanghai: Presbyterian Mission Press, 1927). 32.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Noyes, Harriet. “Rev. Henry Varnum Noyes, D.D.” 25.

[13] Chen, Eugene. Eugene Chen to Harriet Noyes and E. Butler. Guangzhou, China, May 16, 1923. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[14] Cheng, Eileen. “Harriet Newell Noyes: Foreign Pioneer of Women’s Education in Guangdong.” For Women of China, website. All-China Women’s Federation (February 4, 2015). http://www.womenofchina.cn/womenofchina/html1/people/history/1502/159-1.htm.

[15] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to various family members, various locations, 1876. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[16] Cramer, Janet M. “White Womanhood and Religion: Colonial Discourse in the U.S. Women’s Missionary Press, 1869-1914.” In The Harvard Journal of Communication. 14 (2003). 210.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid., 213.

[19] Ibid., 214.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Sarah Noyes, Guangzhou, China, June 3, 1868. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.