Harriet Noyes and Her Work

Introduction

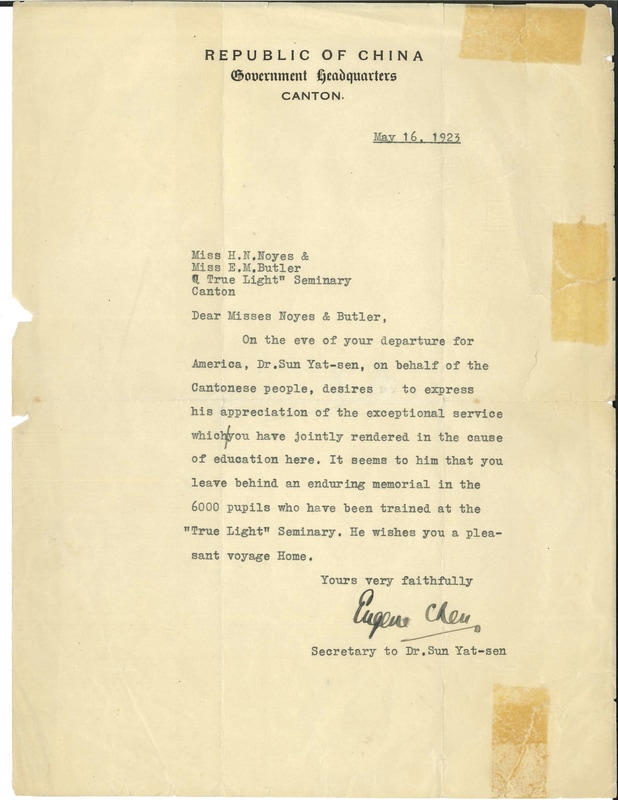

Harriet Newell Noyes (1844-1924) was from Seville, Ohio—a small village roughly forty miles south of Cleveland, her father moved her family to the small village in Ohio in 1840 to be the village’s first Presbyterian minister. Harriet, during her youth, from what can be gleaned from the archival collection containing her manuscript materials[i] (mostly correspondence, some journals), led a life like many young, white, upper middle-class protestant girls at the time. She believed ardently in the word of God as guided through Presbyterian theology and praxis, and believed she needed to serve God every day in her own life. During the Civil War, Harriet worked in some capacity helping with the Union effort in the war, and spent some time being hospitalized or as a nurse.[ii] After the Civil War, Harriet found her calling and decided to spend her life as a missionary for the Presbyterian Church, specifically, the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Upon being accepted by the Board, Harriet was assigned to be a missionary to Guangzhou, Guangdong province, China (廣東省廣州市), then referred to by English-speakers as Canton. Harriet arrived in Guangzhou in January of 1868, beginning her nearly 56 years as a missionary. Quickly learning to speak Cantonese, the local dialect of Chinese spoken in Guangzhou, Harriet then began to work in what she saw as improving education in the region. Harriet opened a number of day-schools in different neighborhoods of Guangzhou, and in 1872, opened the first Christian boarding school for women and girls in the region, and possibly in all of China. Harriet Noyes’ influence grew in missionary and other Christian communities over her time in Guangzhou, eventually being thanked by revolutionary Dr. Sun Yat-sen via his secretary.[iii] In this paper, I will be examining forces, as well as choices and values, that led Harriet Noyes to become a missionary in China. I also look to examine to some degree the compensation of women missionaries compared to that of men.

Harriet Newell Noyes (1844-1924) was from Seville, Ohio—a small village roughly forty miles south of Cleveland, her father moved her family to the small village in Ohio in 1840 to be the village’s first Presbyterian minister. Harriet, during her youth, from what can be gleaned from the archival collection containing her manuscript materials[i] (mostly correspondence, some journals), led a life like many young, white, upper middle-class protestant girls at the time. She believed ardently in the word of God as guided through Presbyterian theology and praxis, and believed she needed to serve God every day in her own life. During the Civil War, Harriet worked in some capacity helping with the Union effort in the war, and spent some time being hospitalized or as a nurse.[ii] After the Civil War, Harriet found her calling and decided to spend her life as a missionary for the Presbyterian Church, specifically, the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Upon being accepted by the Board, Harriet was assigned to be a missionary to Guangzhou, Guangdong province, China (廣東省廣州市), then referred to by English-speakers as Canton. Harriet arrived in Guangzhou in January of 1868, beginning her nearly 56 years as a missionary. Quickly learning to speak Cantonese, the local dialect of Chinese spoken in Guangzhou, Harriet then began to work in what she saw as improving education in the region. Harriet opened a number of day-schools in different neighborhoods of Guangzhou, and in 1872, opened the first Christian boarding school for women and girls in the region, and possibly in all of China. Harriet Noyes’ influence grew in missionary and other Christian communities over her time in Guangzhou, eventually being thanked by revolutionary Dr. Sun Yat-sen via his secretary.[iii] In this paper, I will be examining forces, as well as choices and values, that led Harriet Noyes to become a missionary in China. I also look to examine to some degree the compensation of women missionaries compared to that of men.

Harriet and Imperialism

Although I will be examining forces, choices, and values that led Harriet Noyes to be a missionary in China, I must first briefly address the implications of Harriet’s work as a missionary, specifically how Harriet was acting as a colonizer in a non-western land through her mission work. I will also be addressing this issue in greater depth in the Biography section of this website. One such dimension of the issue of Harriet’s work being that of a colonizer is the idea of a White savior construct—and according to Cramer, “…observations of difference were coupled with the attitude missionary women held that women in other countries…needed to be ‘Whitened’ with the influence of the Christian Gospel.”[iv] The blatant racist attitudes that many missionary women worked within as described by Cramer is reflected in Harriet and her work—several letters in the Noyes Collection written by her contain explicit condemnation of Chinese cultural practices and norms, and she frequently refers to China as a “heathen nation” as well. In addition to this, Harriet begins her work after militarized colonial forces (British, American, French, and German) began to demand access to Chinese land and ports for free trade, a trend that peaked with the Opium Wars. Harriet follows on the coattails of the militarized forces that allowed her to settle in Guangzhou to perform her mission work. It should be noted, that although she was recognized much later in her career for the work she did by the founder of the Republic of China, that her work was not often well-received, as was the work of most other missionaries. In her history of the South China Mission where she worked, she recounts several occasions where villages would band together and pledge to kill anyone who brought any foreigners to their village—a clear reaction to the militarized imperial forces acting upon China at this time.

Although I will be examining forces, choices, and values that led Harriet Noyes to be a missionary in China, I must first briefly address the implications of Harriet’s work as a missionary, specifically how Harriet was acting as a colonizer in a non-western land through her mission work. I will also be addressing this issue in greater depth in the Biography section of this website. One such dimension of the issue of Harriet’s work being that of a colonizer is the idea of a White savior construct—and according to Cramer, “…observations of difference were coupled with the attitude missionary women held that women in other countries…needed to be ‘Whitened’ with the influence of the Christian Gospel.”[iv] The blatant racist attitudes that many missionary women worked within as described by Cramer is reflected in Harriet and her work—several letters in the Noyes Collection written by her contain explicit condemnation of Chinese cultural practices and norms, and she frequently refers to China as a “heathen nation” as well. In addition to this, Harriet begins her work after militarized colonial forces (British, American, French, and German) began to demand access to Chinese land and ports for free trade, a trend that peaked with the Opium Wars. Harriet follows on the coattails of the militarized forces that allowed her to settle in Guangzhou to perform her mission work. It should be noted, that although she was recognized much later in her career for the work she did by the founder of the Republic of China, that her work was not often well-received, as was the work of most other missionaries. In her history of the South China Mission where she worked, she recounts several occasions where villages would band together and pledge to kill anyone who brought any foreigners to their village—a clear reaction to the militarized imperial forces acting upon China at this time.

Harriet and Work

However, I will now focus on the forces, choices, and values that led Harriet to work as a missionary in China—specifically relating to her gender, class, and historical context. During the period when Harriet was growing up, about 1848-1860, and beyond, white, upper-middle class women had comparably very few opportunities for working outside the home, and for someone like Harriet who did not wish to marry, but instead lead a life dedicated to what she saw as the word of the Lord, the options available were especially few. However, although options were limited for white upper-middle class women during this period, mission work did prove to be one outlet where women could lead full, dedicated careers specific to their interests—often in education or medicine, and sometimes in preaching. The opportunities for women to be fully-educated doctors as missionaries was much greater than if they stayed in the United States—at the end of the 19th century, nearly one-third of missionary doctors were women, whereas back home at the states, the number rested around three percent.[v]

This trend translated to other forms of work, like education and education administration—the work that Harriet engaged in. Harriet worked from the onset of becoming a missionary in the education of mostly women and girls, but boys as well, establishing day schools in different neighborhoods of Guangzhou, as well as in the countryside surrounding Guangzhou. She also opened up at least one boarding school that stands to this day, only now in Hong Kong and Kowloon, Hong Kong—the True Light Seminary, founded in 1872.[vi] It is likely that having the ability to have a fully-actualized career that would go somewhat unimpeded due to her gender attracted Harriet in some capacity to the field of mission work for the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions.

Harriet mentions several times of her sympathies to what was then called “The Woman’s Crusade,” what is now deemed the first wave of feminism. In one such letter that she mentions early feminist actions, that she “rejoice[s] always in ‘Woman’s Work’ for good, and it seems as if those who do not sympathize with it might at last stand out of the way.”[vii] From these mentions of the “Woman’s Crusade,” it can be assumed that Harriet understood to at least some degree the power of misogyny in the United States, possibly playing into her decision to become a missionary for the Presbyterian Church.

However, although Harriet’s career may have been relatively unimpeded due to her gender, this does not mean that her pay was anywhere near that of a single man working as a missionary in China at the time. In 1871, the rate of pay for single men was set at $600.00 per year, whereas the salary of an unmarried woman was set at $400.00 per year.[viii] Furthermore, for women who were married and performing mission work, there is a possibility that their work went uncompensated. In the same letter Harriet discusses the compensation of unmarried men and women, she mentions the compensation of married men—set at $900.00 per year with an additional $100.00 per child, but married women are not mentioned. Because of this, as well as the historical context of the time, it quite possible, as stated above, that married women missionaries’ work went uncompensated, even though, as evidenced through The Noyes Collection, married women did much of the work for the mission—whether it be reproductive labor for men and other women missionaries, or actual mission work, disseminating biblical materials, street preaching, training women in the bible, and teaching women and children in schools.

Albeit quite problematic, a value that led to Harriet working in China as a missionary was one guided by racism, briefly discussed above in the section titled “Harriet and Imperialism.” This motivation is what Cramer described as the desire to Christianize, and hence, “whiten” the people of China through mission work. It is clear, as stated above, that Harriet holds rather racist views about the people of China, frequently calling the entire nation dirty and heathen, as well as the condemnation of cultural practices. This racist point-of-view, seeing Chinese people as needing to be saved, was also likely a major motivation in becoming a missionary, specifically coupled with the Christian doctrine of the conversion of others to Christianity. Harriet often expressed that she felt she was saving the Chinese people with whom she worked to convert through education, fully supporting the concept of white saviorhood.

The final aspect of what led Harriet to be a missionary for the Presbyterian Church that I will examine is the choices she made—in regards to education, work, and religion, and how those choices may have been shaped by the sociopolitical context in which she lived. Harriet lived in a time when women in her socioeconomic bracket were beginning to gain access to higher education, but due to her geographic location and the time when she was looking to launch her own life, as well as due to the constraints of her religion’s higher education opportunities, she likely was not able to enter a college or university to begin studying. The closest Presbyterian college to Harriet, who lived in rural Ohio at the time, was The College of Wooster, which did not open for classes until 1870—two years after she departed for China. Additionally, after working in some capacity for the Union during the Civil War, she chose to spend her life dedicated to working for God. For someone like Harriet being raised by a Presbyterian minister, it is not surprising that she chose to work as a missionary.

However, I will now focus on the forces, choices, and values that led Harriet to work as a missionary in China—specifically relating to her gender, class, and historical context. During the period when Harriet was growing up, about 1848-1860, and beyond, white, upper-middle class women had comparably very few opportunities for working outside the home, and for someone like Harriet who did not wish to marry, but instead lead a life dedicated to what she saw as the word of the Lord, the options available were especially few. However, although options were limited for white upper-middle class women during this period, mission work did prove to be one outlet where women could lead full, dedicated careers specific to their interests—often in education or medicine, and sometimes in preaching. The opportunities for women to be fully-educated doctors as missionaries was much greater than if they stayed in the United States—at the end of the 19th century, nearly one-third of missionary doctors were women, whereas back home at the states, the number rested around three percent.[v]

This trend translated to other forms of work, like education and education administration—the work that Harriet engaged in. Harriet worked from the onset of becoming a missionary in the education of mostly women and girls, but boys as well, establishing day schools in different neighborhoods of Guangzhou, as well as in the countryside surrounding Guangzhou. She also opened up at least one boarding school that stands to this day, only now in Hong Kong and Kowloon, Hong Kong—the True Light Seminary, founded in 1872.[vi] It is likely that having the ability to have a fully-actualized career that would go somewhat unimpeded due to her gender attracted Harriet in some capacity to the field of mission work for the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions.

Harriet mentions several times of her sympathies to what was then called “The Woman’s Crusade,” what is now deemed the first wave of feminism. In one such letter that she mentions early feminist actions, that she “rejoice[s] always in ‘Woman’s Work’ for good, and it seems as if those who do not sympathize with it might at last stand out of the way.”[vii] From these mentions of the “Woman’s Crusade,” it can be assumed that Harriet understood to at least some degree the power of misogyny in the United States, possibly playing into her decision to become a missionary for the Presbyterian Church.

However, although Harriet’s career may have been relatively unimpeded due to her gender, this does not mean that her pay was anywhere near that of a single man working as a missionary in China at the time. In 1871, the rate of pay for single men was set at $600.00 per year, whereas the salary of an unmarried woman was set at $400.00 per year.[viii] Furthermore, for women who were married and performing mission work, there is a possibility that their work went uncompensated. In the same letter Harriet discusses the compensation of unmarried men and women, she mentions the compensation of married men—set at $900.00 per year with an additional $100.00 per child, but married women are not mentioned. Because of this, as well as the historical context of the time, it quite possible, as stated above, that married women missionaries’ work went uncompensated, even though, as evidenced through The Noyes Collection, married women did much of the work for the mission—whether it be reproductive labor for men and other women missionaries, or actual mission work, disseminating biblical materials, street preaching, training women in the bible, and teaching women and children in schools.

Albeit quite problematic, a value that led to Harriet working in China as a missionary was one guided by racism, briefly discussed above in the section titled “Harriet and Imperialism.” This motivation is what Cramer described as the desire to Christianize, and hence, “whiten” the people of China through mission work. It is clear, as stated above, that Harriet holds rather racist views about the people of China, frequently calling the entire nation dirty and heathen, as well as the condemnation of cultural practices. This racist point-of-view, seeing Chinese people as needing to be saved, was also likely a major motivation in becoming a missionary, specifically coupled with the Christian doctrine of the conversion of others to Christianity. Harriet often expressed that she felt she was saving the Chinese people with whom she worked to convert through education, fully supporting the concept of white saviorhood.

The final aspect of what led Harriet to be a missionary for the Presbyterian Church that I will examine is the choices she made—in regards to education, work, and religion, and how those choices may have been shaped by the sociopolitical context in which she lived. Harriet lived in a time when women in her socioeconomic bracket were beginning to gain access to higher education, but due to her geographic location and the time when she was looking to launch her own life, as well as due to the constraints of her religion’s higher education opportunities, she likely was not able to enter a college or university to begin studying. The closest Presbyterian college to Harriet, who lived in rural Ohio at the time, was The College of Wooster, which did not open for classes until 1870—two years after she departed for China. Additionally, after working in some capacity for the Union during the Civil War, she chose to spend her life dedicated to working for God. For someone like Harriet being raised by a Presbyterian minister, it is not surprising that she chose to work as a missionary.

Conclusion

Harriet Noyes has, until this time, had almost no formal scholarship or research done on her life, her work, or the impact she had in China. She has been claimed by some, including the All-China Women’s Federation, to be a pioneer in women’s education in China.[i] Her work lasted nearly fifty-six years, from 1868 to 1923, nearly until the time of her death in January of 1924. Although much can be said about the imperialist implications of her mission work, it should also be understood that a number of forces, choices, and values led her to her mission work, including patriarchal forces limiting white, upper-middle class women’s abilities to enter formalized work forces. Because of these patriarchal forces, many women began to turn to missionary work at home and abroad—and Harriet was one of these many women.

Harriet Noyes has, until this time, had almost no formal scholarship or research done on her life, her work, or the impact she had in China. She has been claimed by some, including the All-China Women’s Federation, to be a pioneer in women’s education in China.[i] Her work lasted nearly fifty-six years, from 1868 to 1923, nearly until the time of her death in January of 1924. Although much can be said about the imperialist implications of her mission work, it should also be understood that a number of forces, choices, and values led her to her mission work, including patriarchal forces limiting white, upper-middle class women’s abilities to enter formalized work forces. Because of these patriarchal forces, many women began to turn to missionary work at home and abroad—and Harriet was one of these many women.

Citations

[i] The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[ii] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Edward Noyes, Guangzhou, China, December 11, 1868. In The Noyes Collection, Box 1, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[iii] Chen, Eugene. Eugene Chen to Harriet Noyes and E. Butler, Guangzhou, China, May 16, 1923. The Noyes Collection, Box 5, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[iv] Cramer, Janet M. “White Womanhood and Religion: Colonial Discourse in the U.S. Women’s Missionary Press, 1869-1904.” In The Howard Journal of Communications. 14 (2003). P. 214.

[v] “’Lady’ Physicians in the Field: Women Doctors and Presbyterian Foreign Mission Work, 1870-1960.” In The Journal of Presbyterian History. 82 no. 4 (Winter 2004). P. 271.

[vi] Noyes, Harriet. “Chapter III: Difficulties and Hindrances.” In The History of the South China Mission. (Shanghai: Presbyterian Mission Press, 1927). P. 32.

[vii] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Mary Noyes, Guangzhou, China, July 27, 1874. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[viii] Noyes, Harriet. Harriet Noyes to Mary Noyes, Guangzhou, China, July 10, 1871. In The Noyes Collection, The College of Wooster Department of Special Collections, Wooster, Ohio.

[ix] Cheng, Eileen. “Harriet Newell Noyes: Foreign Pioneer of Women’s Education in Guangdong.” For Women of China. Website. All China Women’s Federation (February 4, 2015). http://www.womenofchina.cn/womenofchina/html1/people/history/1502/159-1.htm.